For anyone new to Adam’s story, here’s an introduction.

I’m tired of real-life politics at the moment, so why don’t we talk about fictional politics instead?

In previous versions of the Lance Eliot saga, the politics of my imaginary kingdom were simplistic. This time around, I want to craft a more complex political situation for Lance and his companions to navigate.

If this sounds boring, don’t worry! The Lance Eliot saga shan’t be a political thriller, but an adventure story with a sprinkling of political drama. I’m still planning dragons, swordfights, and Other Cool Stuff that I won’t discuss yet; it shan’t all be politics! I just want to create a setting for Lance’s adventures that’s more believable than a generic fairy-tale kingdom.

The Lance Eliot saga takes place mostly on Fyrel, an hourglass-shaped continent in the world of Gea. The northern and southern landmasses are joined at the equator by an isthmus. This strip of land, bordered by ocean on the east and west, is the kingdom of Guardia: a gateway between the northern and southern lands.

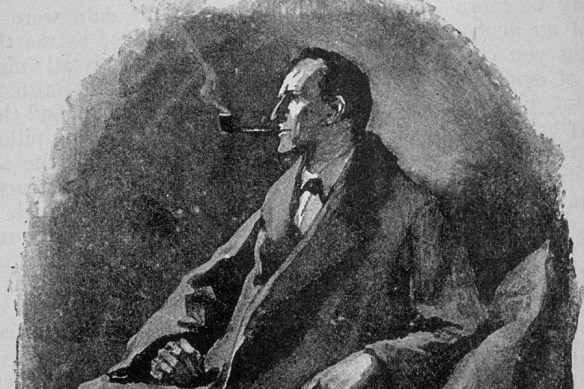

I’m working on an updated map for Guardia. For now, here’s the map I used for previous versions of the Lance Eliot story.

Guardia is bordered by two vast empires: Tyria to the north, and Sanguin to the south. These world powers expanded over centuries to completely conquer the northern and southern landmasses. Only the ocean and the little kingdom of Guardia separate them.

For such a small nation, Guardia is remarkably defensible. Its northern border is largely blocked by mountains and dense jungles; the southern border consists mostly of mountains, deserts, and dangerous marshes. The south is also bordered by a narrow strip of territory known as the Noman’s Land: a lawless neutral zone.

Thanks to its place between two empires, Guardia regulates trade and traffic between North and South. Money, goods, merchants, and travelers—all carefully supervised—flow through the kingdom like sand through the neck of an hourglass. Guardia’s economy, built painstakingly over centuries, depends almost entirely on trade.

The healthy economy funds a strong navy and military to protect the kingdom. Guardia exists in a delicate balance, suspended between two warlike empires, trusting neither, but depending on both.

Tyria and Sanguin are both eager to expand, but conquest is earned by war, and Guardia is the only avenue through which war can be fought. As long as it remains free, shielded by its hostile terrain and strong military, Tyria and Sanguin can’t attack each other.* These empires are locked in a cold war. If either declares war on Guardia itself as a prelude to further conquests, the other empire will immediately fight to defend it.

Guardia’s status as a merchant nation, protected by its military and impenetrable borders, are all that prevents a world war.

None of this has anything to do with Lance Eliot. He doesn’t really care—he’s just a college student in a little Indiana town. Guardia’s politics are not his problem. Gea isn’t even his world. His journey to Gea was a mistake: a supernatural screw-up by someone who tried to invoke Lancelot, the hero of Camelot, but got Lance instead.

Lance Eliot was summoned to Guardia on the order of Eisen, a military leader forced into early retirement by Demas, the King. Eisen retreated to the city of Faurum and founded the Guardian Peace Committee. The purpose of this secret society is to maintain Guardia’s independence, preventing war between the North and South.

King Demas has reigned for decades, keeping the peace with both empires, but rumors have reached Eisen that the King is considering a secret deal to surrender Guardia to Tyria in exchange for personal favors. If Tyria annexes Guardia, Sanguin will retaliate, and war will erupt.

If the King is not stopped, Guardia will become a battleground: a land of blood and ashes trampled by armies.

Eisen doesn’t have a lot of resources. The Guardian Peace Committee has only a small military force of its own. (This includes Tsurugi, a disgraced soldier in Eisen’s service.) With few options, Eisen employs the supernatural gifts of a young woman, Maia, to search beyond Gea for someone—anyone—who can help.

Enter Lancelot of Camelot. By all accounts, this legendary knight of Earth possessed both martial prowess and political savvy. If Maia can use her powers to summon Lancelot and break the language barrier, perhaps he can offer Eisen support, or at least some advice.

Of course, Maia makes the mistake of summoning Lance Eliot instead of Lancelot, and the rest is history… or shall be history once I get around to writing it.

*Neither Tyria nor Sanguin can wage war with the other entirely by sea: it’s far too costly to transport entire armies, with provisions and war machines, hundreds of miles in boats. Apart from the dangers of sea travel, any force small enough to travel in ships would be quickly outnumbered in enemy territory, unable to retreat. The only viable strategy for waging war is through Guardia.