Those Christians, I tell you! They’re all so evil. All of them! If you don’t believe me, just switch on the television or go to the movies. Hollywood proves that Christians are evil, because Christians are often depicted as villains, and the media is always right.

Right?

Seriously, though—why are Christians so often portrayed as horrible people in the media? Why are books, movies, TV shows, and video games full of perverted priests, prejudiced pastors, and sinister ministers?

Consider Warden Norton from The Shawshank Redemption, a film based on a story by Stephen King. (I haven’t read any of his books, but I’ve heard Stephen King uses Bible-thumping Christians as a lot of his villains.) Warden Norton is an awful person. He mistreats prisoners in his care, denies them justice, accepts kickbacks, murders people, and generally makes himself unpleasant. All the while, he quotes the Bible and assumes God is on his side.

God loves you, but Warden Norton will probably shoot you in the face.

Even when Christians in fiction aren’t evil, they’re often well-meaning but ignorant simpletons. Take Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. I really enjoyed the series, but one episode irritated me. It was the episode featuring a Christian, and she was a bland, weepy, superstitious ditz.

Why are Christians portrayed so badly in the media? There are actually quite a few reasons.

It can be ironic or scary when a supposedly “good” person is evil.

There’s an artistic irony when a righteous person is actually wicked. It’s also pretty freaking scary. Who isn’t disturbed when a good person turns out to be a bad one?

Religious people have power and influence, which makes them great villains.

Priest and pastors have influence over groups of people. What happens when religious leaders are evil? They command the loyalty of their followers—even when that loyalty is innocent or well-intentioned. Religious leaders have power and authority, which can be easily turned to wicked ends.

Religious people sometimes do horrible things.

I hate to say it, but there’s a little truth in the portrayal of priests as pedophiles and preachers as charlatans. Christians, and people who call themselves Christians, have done some awful things. The media reflects that.

No secular media group wants to be accused of proselytizing.

Media groups exist to make money. Unless they produce religious media, these companies don’t want to be accused of pandering to Christians or spreading religious propaganda. Creating a genuinely Christian character puts media groups at risk of seeming to push a religious agenda. It’s safer to fall back upon familiar stereotypes like the evil or ignorant Christian.

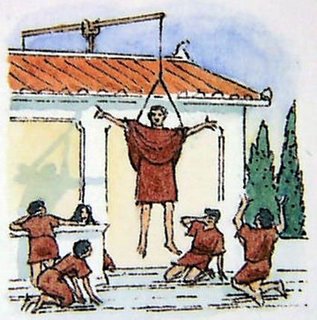

Some religious traditions are spooky.

Have you ever stepped into an old-fashioned cathedral? You should try it. Little noises are echoed and magnified. Candles light the vast, empty gloom. Stained glass windows depict sad, soulless saints. Somber Christs hang in perpetual agony on crosses and crucifixes. Some Christian customs and traditions are frankly a bit creepy. They really build an atmosphere for villainy.

Some people just hate religion.

I’m looking at you, Philip Pullman.

As much as I understand these reasons for creating lousy Christian characters, I’m tired of the stereotypes. Am I the only one who thinks most depictions of Christians in the media are offensive? If other groups were so badly stereotyped, there would be outrage. Why is it socially acceptable to portray Christians as universally evil or ignorant?

It’s a problem, and I have two suggestions for resolving it.

First, do your research and create Christian characters that actually represent Christianity.

I’ve already touched upon this, but I’ll say it anyway: religious stereotypes are not only offensive, but usually incorrect. Joss Whedon, God bless him, understands this. Whedon is an atheist, yet he created a character named Shepherd Book who is genuinely Christlike.

Shepherd Book demonstrates a good understanding of Christian doctrines, and an equally good sense of humor. He is devout, patient, kind, and generous. To put it simply, Shepherd Book is represented by the media as a great character and a good Christian. It can be done.

Learn from the good Shepherd.

I’m not asking anyone in the media to create religious propaganda. I’m asking everyone in the media to create Christian characters that aren’t shameless hypocrites, greedy shysters, arrogant bigots, filthy perverts, sociopathic lunatics, or well-intentioned idiots. Is that really so much to ask?

Second, it’s perfectly fine to create characters that are evil Christians—just don’t be lazy about it.

I occasionally recommend an anime called Trigun. Set on an arid planet in the distant future, Trigun is basically the Old West in space. My favorite things about the show are its two main characters, Vash the Stampede and Nicholas D. Wolfwood, and their strained friendship.

Vash is an expert marksman, unbridled optimist, and wandering hero. He lives by a philosophy of “love and peace,” refusing to kill anyone. “Ain’t it better if we all live?” he asks.

Vash and his philosophy are tested by Wolfwood, an itinerant preacher who carries a literal cross wherever he goes. (When a bystander remarks that the cross is heavy, Wolfwood quips, “That, my friend, is because it’s so full of mercy.”) Despite his merciful profession, Wolfwood’s philosophy is a harsh one. There’s an Old Testament justice in his actions. He won’t hesitate to execute a bad man.

You do not want to cross this man. (Pun intended. I’m so, so sorry.)

The thing about Wolfwood is that he himself is a bad man. He drinks, smokes, sleeps around, and kills quite a number of people. (Wolfwood’s cross is actually a machine gun with compartments for handguns, which is either blasphemous or awesome.) Even his theology is flawed. However, in spite of his faults, Wolfwood is a complex character. He sees violence as a necessity, and regards the world’s evils (and his own) with determined resignation.

To put it simply, Nicholas D. Wolfwood is a good bad Christian. He manages to be a Christian and a bad person without ever becoming an insulting stereotype. It doesn’t take offensive clichés to portray Christians as bad people. It can be done.

Christians are generally depicted very badly in the media. That needs to change. Christians—even the bad ones—can be treated fairly, and they deserve to be.