It has been a while since TMTF’s last Review Roundup. Why don’t we look at some stories about death games?

In these media, protagonists gamble their lives in dangerous games. Some of these are literal: formal competitions with rules. Some are figurative: risky ventures into crime. And one of these stories has nothing at all to do with death games. (I enjoy writing these reviews, but not enough to plan my media consumption around them!)

Let’s talk about The Hunger Games trilogy, Ant-Man, The Big Lebowski, Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon?, and Whisper of the Heart.

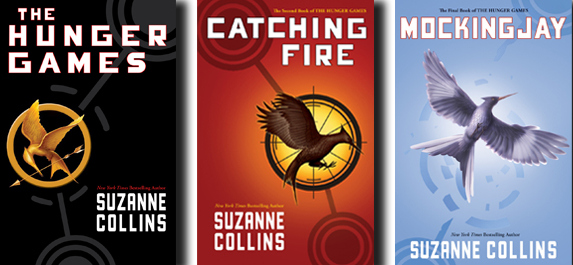

The Hunger Games trilogy

For the first time in years, I picked up a popular Young Adult novel to find out what all the fuss is about. (My last investigation of a literary sensation led me to read Twilight, a mistake from which I never fully recovered.) The Hunger Games is a pop culture phenomenon, and I meant to find out why.

For the first time in years, I picked up a popular Young Adult novel to find out what all the fuss is about. (My last investigation of a literary sensation led me to read Twilight, a mistake from which I never fully recovered.) The Hunger Games is a pop culture phenomenon, and I meant to find out why.

I dunno, guys. I wasn’t all that impressed. Maybe I’m just a grumpy snob, but the Hunger Games trilogy neither dazzled nor entertained me. The books aren’t bad, but I wouldn’t call them classics.

The Hunger Games books tell the tale of Katniss Everdeen, a pragmatic teen trapped in an impoverished district of Panem. The government of this dystopian country rules its outer districts by fear and humiliation, selecting two children from each district every year and forcing them all to fight to the death. This gruesome event, the Hunger Games, is televised throughout Panem as an amusement for the wealthy; for the poor, it’s a reminder of their powerlessness. Katniss is selected for the Hunger Games, and the books follow her rise and fall from gladiator to celebrity to revolutionary to whiny PTSD victim.

The Hunger Games books are lauded for their smart setup and gripping story. I’ll be the first to admit there is truth to these praises. Panem is an interesting setting. The concept of the Hunger Games is fascinating, providing a way for a corrupt government to placate the rich and subjugate the poor. The story has its twists and turns, and the first book is actually pretty engaging.

However, the characters are mostly dull and unlikable. Katniss, who narrates the story, lacks much personality besides a coldly analytical attitude and occasional flickers of affection. As the books wear on, Katniss is traumatized by her horrific experiences, becoming angsty and angry—a change in her personality, sure, but not for the better. More promising characters, such as foppish Effie Trinket and drunken Haymitch Abernathy, end up disappointing.

When it comes to tone and style, I get the impression the Hunger Games books aren’t sure what they want to be. They have a sort of gritty realism concerning poverty and war. I appreciate that. However, this gloomy approach is at odds with the books’ ludicrous sci-fi touches and predictable Young Adult nonsense. (Yes, there’s a love triangle, and it’s annoying.)

In the end, the Hunger Games books have just enough harsh realism to be depressing and just enough teen kitsch not to be taken seriously. They fall in a literary no man’s land, refusing to embrace either realism or sensationalism, and embodying the worst traits of both. I find it hard to recommend these books.

Ant-Man

Moving on to something much more entertaining, Ant-Man is another big, dumb, spectacularly fun Marvel movie. Unlike the Hunger Games books, Ant-Man embraces its own goofiness in a way that’s a joy to see.

Moving on to something much more entertaining, Ant-Man is another big, dumb, spectacularly fun Marvel movie. Unlike the Hunger Games books, Ant-Man embraces its own goofiness in a way that’s a joy to see.

Ant-Man begins with Scott Lang feeling very small. This well-meaning ex-convict can’t keep a job or convince his ex-wife to let him spend time with their little girl. When Lang meets an old inventor named Hank Pym—he burgles Pym’s home, actually, but that’s not the point—Pym offers him “a shot at redemption,” meaning an opportunity to put on a high-tech suit, shrink to the size of an ant, and dive back into the life-or-death game of high-stakes burglary.

Look, if you’ve seen any recent Marvel movie, you know what to expect at this point. Ant-Man is full of quotable quips, flashy action scenes, and comic book lore, with a little sentimentality sprinkled here and there.

This time, however, there are two things to make the film stand out. First is an emphasis on father-daughter relationships. This motif isn’t developed as fully as a it could be, but it works. The second thing is that Ant-Man is basically a superhero heist movie, in the same way the first Captain America is a superhero war film and the second one is a superhero cold war thriller. Ant-Man isn’t about saving the world, but stealing stuff… to save the world, I guess.

It’s still a nice touch.

I really enjoyed Ant-Man. It nods at other movies in the Marvel Cinematic Universe without depending on them, and I look forward to seeing Ant-Man in future films. Not bad for such a little guy.

The Big Lebowski

With that, we move on from a small hero to a larger-than-life one in The Big Lebowski. Ironically, however, the film’s hero isn’t actually the Big Lebowski, but a slacker with the same name (I’ll call him the Lesser Lebowski) who loves bowling, booze, and tacking the word “man” to the end of nearly every sentence.

With that, we move on from a small hero to a larger-than-life one in The Big Lebowski. Ironically, however, the film’s hero isn’t actually the Big Lebowski, but a slacker with the same name (I’ll call him the Lesser Lebowski) who loves bowling, booze, and tacking the word “man” to the end of nearly every sentence.

The Big Lebowski begins when thugs storm the home of Jeff Lebowski, a laid-back stoner known as “the Dude,” and pee on his rug. It was a nice rug, man. It really tied the room together. The thugs threatened the Dude (and peed on his rug) under the impression he was “the Big Lebowski,” a millionaire with the same name. When the Dude takes his bowling buddies’ advice to seek compensation from the Big Lebowski for the rug, he becomes snared in a game of deception, violence, kidnapping, cursing, and postmodern art.

This movie is sort of a black comedy and sort of a noir crime film, but it’s mostly Jeff Bridges bowling, drinking, and wandering around Los Angeles. In the end, the film’s complex web of crime and deception unravels to reveal a whole lot of nothing, and I think that’s the point: there never was one.

This was quite an entertaining movie. It ain’t one for kids—it has bullets, boobs, and f-bombs beyond count—but for adults with a healthy sense of the absurd, The Big Lebowski is a treat.

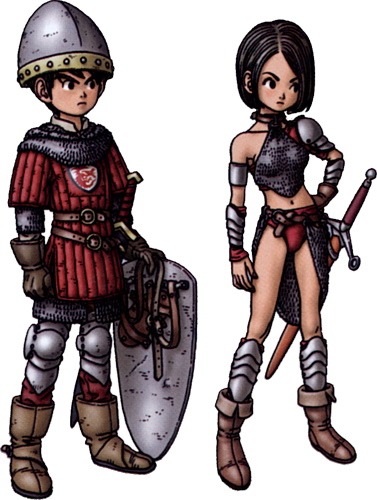

Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon?

Well, is it?

Well, is it?

The oddly-titled anime Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon? is the tale of Bell, a nice young man who longs to become an adventurer—to impress the ladies, of course. He lives in a medieval fantasy town whose existence revolves around the eponymous dungeon: a labyrinth teeming with monsters. Adventurers join familias—guilds sponsored by gods or goddesses—and venture into the dungeon in a dangerous game for treasure and glory. In quest to become a dungeon-conquering hero, Bell accepts the sponsorship of a down-on-her-luck goddess named Hestia. This unlikely pair must work together for Bell to have any chance of becoming a master adventurer and impressing the ladies… well, one in particular.

I won’t lie, guys. This anime is incredibly dumb. Remember what I said about Ant-Man embracing its goofiness? This show does the same, but with roughly ten thousand times as much enthusiasm.

I mean, the anime’s opening theme has a momentary scene of Bell and Hestia brushing their teeth. Look at this. Look at it.

This is basically the entire show: dumb as all heck, but endearing in its silliness, with some gratuitous cleavage for good measure.

The world of Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon? functions exactly like a video game (an MMORPG, to be precise) without actually being a video game. Its adventurers gain experience and level up—heck, they even have statistics (appearing as magical tattoos on their backs) reflecting their competency in various areas. Monsters respawn on a set timetable, and powerful creatures explicitly called bosses guard certain floors of the dungeon. The setting is instantly comprehensible to gamers, but at the cost of making absolutely no sense. Why do adventurers level up? What revives the monsters that respawn? What the heck is going on?!

(It is very faintly hinted that the gods and goddesses of ancient times created this video game-like world for their own enjoyment, but no real explanation is ever given.)

This is a show in which half the female characters have crushes on the hero, like Twilight in reverse, and most female adventurers wear stupid chain mail bikinis. I can’t defend or recommend this anime. It’s really, really dumb.

All the same, I kinda enjoyed it. Bell, who has a massive inferiority complex, is kind and friendly: a welcome change of pace from angsty or arrogant anime heroes. Hestia works odd jobs to support him, despite being, y’know, a goddess. The show seldom takes itself too seriously; the rare occasions it does are some of its weaker moments. For the most part, its good-natured goofiness made it fun to watch, if not intellectually rewarding.

Whisper of the Heart

At last we arrive at a film that not even I can pretend fits the vague “death game” theme of this Review Roundup: Whisper of the Heart. Because of this movie, John Denver’s all-American classic “Take Me Home, Country Roads” will forever remind me of urban Japan.

At last we arrive at a film that not even I can pretend fits the vague “death game” theme of this Review Roundup: Whisper of the Heart. Because of this movie, John Denver’s all-American classic “Take Me Home, Country Roads” will forever remind me of urban Japan.

Shizuku is a bookish Japanese teen, sharing a cramped apartment with her family. She notices one day that all of her library books were previously checked out by someone named Seiji, and wonders who he might be. Shizuku later ends up at an antique shop. Its owner encourages her to pursue her passion for writing stories, and also introduces her to his grandson: the mysterious Seiji. As Shizuku’s love of writing grows, so does another kind of love.

Studio Ghibli is magnificent. Whisper of the Heart was one of the few Studio Ghibli films I had never seen, and I’m glad I finally watched it.

I’ll be honest: Whisper of the Heart is no masterpiece. Nah, it’s merely a touching, charming, beautifully-animated coming-of-age story with a scene that nearly brought tears to my cynical eyes. By lofty Studio Ghibli standards, this is merely a decent film. By any other standards, Whisper of the Heart is wonderful.

I enjoyed the film probably more than most people because I identify with Shizuku’s desire to write stories. I was Shizuku once, in a manner of speaking: young, naïve, hopeful, insecure, eager to share my stories, and scared no one would want to read them—or worse, that they wouldn’t be worth reading.

Whisper of the Heart has its fair share of sentimentality: far more, in fact, than nearly any other Studio Ghibli film. The movie lacks the effortless grace and emotional punch of the studio’s finest works… but there is one scene, in which several musicians strike up their instruments for a joyful, impromptu performance of “Take Me Home, Country Roads,” that brought me closer to crying than any film in recent memory (except Inside Out, of course).

It may not be as popular as Studio Ghibli’s other movies, but Whisper of the Heart is absolutely worth watching, especially if you’re an aspiring writer, a Studio Ghibli fan, or a fan of romance.

What books, films, shows, or video games have you enjoyed lately? Let us know in the comments!